The Service Tree: Exploring Boundaries and Release through Yew, by Natalia Schwien

It’s likely that if you live in an urban area, you regularly pass a familiar unassuming friend – the yew.

Most commonly overlooked as a hedge, this boundary keeper is called ēo or Idho in the Ogham tradition, lubhar in Gaelic, ywen in Welsh. Members of its genus can be found across the globe, native to Europe, Japan, Northwest Africa, the Middle East, and North America.

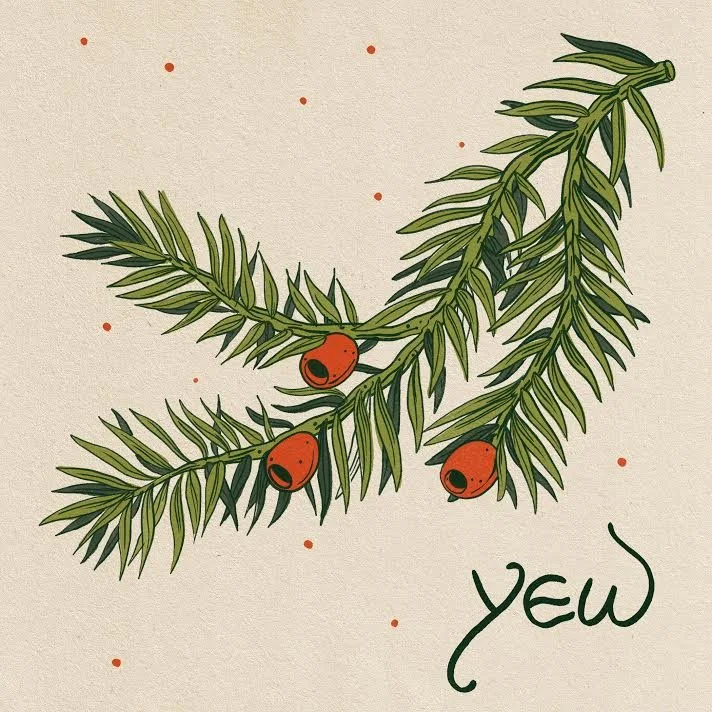

This coniferous ally has soft, deep green needles and bright Crayola red berries, colors with spiritual meaning in numerous ontological traditions. The etymology of its Latin name, Taxus Baccata, is derived from the nominative masculine word taxicum, which is synonymous with ‘poison,’ and baccāta, a feminine word meaning ‘bearing berries.’ The word taxus, the descendant of that ancient term for toxicity, literally only means ‘yew tree.’ With poisonous seeds, poisonous wood, and poisonous needles, this guardian grows in a deadly class of its own.

However, to isolate the Idho as a kind of Grim Reaper would be disrespectful to the trees and to death – both literally and figuratively. For despite toxicity, the chemical compound Paclitaxel, which is derived from its bark, constitutes the basis of the medication Taxol, which blocks the division of cancer cells. Harvesting its bark kills the tree – so its medicine is a gift, a symbol of the impermanence of life, the growth from decay, and bravery in difficult decisions. The fruit, otherwise called the aril, is both delicious and nutritious, but it takes some serious commitment to pick out the deadly seeds, reminding us to pause and ask ourselves if a path or choice we’re considering is truly worth the potential cost.

The ywen is shaped for the purposes of its environment, most regularly spotted lining modest buildings or in rows along sidewalks. I recently moved to Cambridge, MA, after nearly ten years in New York – and I see yew everywhere. The female shrubs have been fruiting, little beacons calling out for emotional catharsis: What can you shed? Are your boundaries holding? Where do you need to be directed? Are you taking time for yourself? Are you listening to your guides? What does the otherworld, what does your higher-self feel?

I’ve greeted this old friend on my way to new spaces full of new humans. It has been deeply comforting to reach out to Idho’s energy in this moment of change, both seasonally and personally, even if it has been manicured into institutional dressing.

But, when allowed to grow unconstrained, wild, the yew embodies sagacity. It illustrates a joyful and thoughtful aging process. Hidden in churchyards across Europe, these ancient beings are guideposts for the continuation of worlds – the very thin veil between life and death, but also between a subsumed pre-Christian holy site and an appropriating church. Many of these old trees rest on ley lines or mark the location of ancient ritual grounds for pagans. The word pagan comes from the Latin paganus, meaning ‘rustic’ which was later joined in its definition with ‘heathen’ under Christian rule. This translation is important because Christianity was an urban movement, divorced from the land. The spiritual traditions of the paganus were Earth-based, completely integrated within their relative landscapes; therefore, as the monotheistic, anthropocentric religion of the Roman Empire spread, and as it was picked up by subsequent invading nations, it proved impossible to entirely stamp out paganism because that would mean destroying the land. So, instead, the early Catholics subsumed and built on top the existing system – absorbing the locations and the calendar dates, shifting many deities into saints, and more. This assimilation went both ways, and new systems of belief emerged. It was thought to be taboo to cut the yews down; thank the guides for ecological and spiritual conservation woven amongst superstition.

Artwork by Alison Czinkota

Vanessa recently shared her experience meeting one such ancestor – the Fortingall Yew, the oldest living being in Europe, over 5,000 years of life. A yew growing at the heart of Scotland’s map, in a churchyard, holding space for a meeting of eras, reminding us that Earth-based practice is still available.

The Ogham Tract or In Lebor Ogaim, an Early and Old Irish text from the 14th Century which chronicled oral traditions from Celtic cultures, pulls “poetic descriptions or kennings that elucidate the meanings of the main sigil-based” pseudo-alphabet, The Ogham. Each of these sigils, or letters, represents a tree along with its associated mythos – and the very last tree is our friend, the yew.

In the old Irish tale, the Dream of Óengus, the mythic hero, whose Anglicized name is Angus, falls in love with Cáer Ibormeith, a zoomorphic woman who transforms along with her she-kin into swans. She lives at the lake of the Dragon’s Mouth, and her name translates to ‘Juicy Yew Berry.’ She personifies the balance of danger and emotional aspirations; it may be perilous to love someone, to love oneself, or to love the world around us, but it may also be deeply rewarding. We probably won’t transform into swans and fly off into the sunset, but maybe we can face the unknown in our lives as well as our deaths with courage and peace, in togetherness.

Celtic mythological characters such as the Ulster druid Morainn call this being Sinem Fedo “oldest tree” and Ibhur “service tree.” The prolific incarnated demigod, Cú Chulainn, designates it as Luth (no lit) lobar.i.aes “strength or energy or color of an infirm person” and “people or an age.” The Macc Óc, or Óengus, the heroic love of Cáer Ibormeith, describes the tree as Cainem sen no aileann ais “fairest of the ancients” or “pleasing consent.” The yew is indeed all of these things.

I love the idea of “pleasing consent,” both in relation to the partnership of Cáer Ibormeith and Óengus, and in association with the impermanence of life blended with the inevitability of death. There is bliss in release. There is pleasure in connecting with the forces that guide us, the conscious world around us, with each other. Our plant and animal neighbors whose life cycles coalesce with our own.

My Celtic Mythology professor used the word ‘liminal’ to describe the yew. From the Latin word limen/limin, meaning ‘threshold,’ liminality is full of potential because it holds the space, the boundaries, on our literal maps and on our personal paths. “Yews often grow upon barrow mounds and places associated with our ancient ancestors as a marker of the world beyond and our eternal spirits…[their] root systems are vast and can be seen disturbing the surface soil in many graveyards, even breaking up the capstones of graves as the centuries pass.” Perhaps the yew is reminding us that the enshrining process is an unnatural one, let us be dust to dust. Let our bodies feed the Earth. Let us enter that liminal space blissfully and in service, like our service tree.

Samhain may have passed, but that does not mean we are shut off from the more-than-human world or from the cycles of release. As we approach the winter, look out for the last of those bright berries and bask in the complicated plentitude of our beautiful interconnected ecosystems.

Quotations: Forest, Danu. Celtic Tree Magic: Ogham Lore and Druid Mysteries. Pg 10, 209.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sacred Warrior apprentice, and soon to be teacher, Natalia Schwien, likes plants and gregorian chants. When she’s not lecturing people about non-human sentience, she’s an herbalist, writer, vocalist, Reiki practitioner, and producer whose work has been featured in New York Magazine, The New Yorker, Vice, Tom Tom Magazine, For The Wild, and more. For the past three years, she’s been training under Sacred Warrior founder, Vanessa Chakour assisting on plant walks, moon meditations, and rewilding retreats in Costa Rica and at the Wolf Conversation Center while helping to organize partnerships in Scotland. She loves howling with the SW fam. After nearly ten years in BK, Natalia is a recent escapee of NYC – now pursuing a Masters in Theology with a focus on the intersection of ecology and spiritual practice at Harvard Divinity School and finishing an MA in English with a focus on fantasy literature through Middlebury at Oxford University. She’s a member of the Harvard Council of Student Sustainability Leaders – and just gave her first solo plant walk! With the hope of helping humans, non-humans, and our planet heal, she recently passed her wildlife rescue and rehabilitation exam and completed the first portion of her doula training. She leads vocal meditations for anxiety release and makes music under the moniker Ellayo. And just for fun, she also makes zero-waste holiday wreaths.